On Stage - Head Table - The Membership - Blacklist - Visitors

|

Richard BallingerGOLD CLUB You buy sixteen tons, and what do you get?

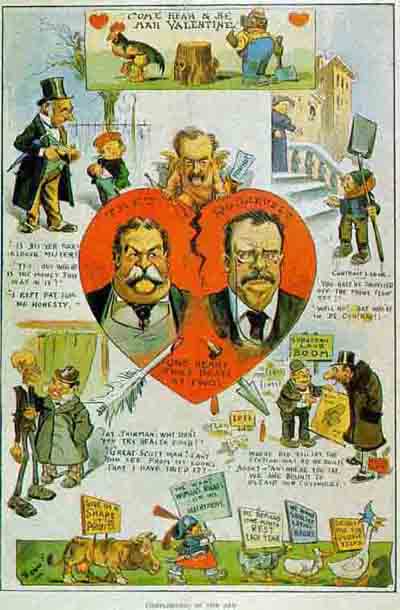

This cropped up on print.google.com, a brief excerpt from a report in the US Congressional Serial Set, 1910, Volume 10. The Set is a collection of documents and reports from the House and Senate. In a search for one S.R. Blonger, located by George Simmonds, agent, it was learned that he, Blonger had moved to Denver, Colorado, but his street address could not be found. A Mrs. Dickson, with whom Blonger formerly roomed here in Seattle, Wash., a negress, stated that she had heard Blonger talk of his coal claim. That he belonged to some sort of club and that the members of the club all had coal claims and handled them on shares. These claims are in Alaska. That Blonger went downtown three or four times to sign some papers in connection with his coal claim. Simon, living in Seattle, apparently owned shares in a large coal claim in Alaska, along with other members of a "club". When we first saw this reference, we thought perhaps Simon had sold someone fake mine stock, or vice versa, and this was testimony from an investigation or trial. Aha, we said. Simon's a swindler! Not so fast. Searching on other names in the short blurb brought other short references, and searching on names in those brought others. Then wider searches on the important names. All the way to Teddy Roosevelt. What's going on here? Time for a history lesson. A great deal of ink has been spilt over the so-called Ballinger-Pinchot controversy, one of the most thoroughly discussed topics in American conservation policy. Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, a vast coal field was discovered in Alaska. Mr. Ballinger and the National Grab Bag, by John L. Mathews, Hampton's Magazine, December 1909 Back of Controller Bay, beginning almost at tidewater and extending inward until they are lost beneath the immense ice masses of Bering and Martin's River Glaciers, extend the coal fields. Near the seashore this coal, which crops out upon the surface, is of a soft, bituminous character about the equal of the best Illinois fuel. A little farther back is found an enormous amount of a semibitummous, coking coal, the equal of Pocahontas, George's Creek, or any other first-class coking coal of West Virginia. And beyond this again lies Carbon Mountain, practically a great mountain of the finest anthracite in the world- probably the largest known deposit of this valuable mineral. The total value of these Controller Bay deposits (and they are but a small part of the total Alaskan coal-fields) is beyond calculation. They have never been surveyed. The coal in sight on Carbon Mountain is in four veins reaching to thirty feet in thickness and extending entirely around and through the mountain. What lies beneath the surface no man knows. All this coal is within an hour of the ship side and can be transshipped to San Francisco for less than Colorado coal can climb the first range of mountains. A vast quantity of this coal is well adapted for use in the vessels of the Pacific Squadron, making these coal lands especially valuable to the government. At present that squadron is supplied with coal from the East. According to law, these lands could be claimed by individuals for $10 or $20 an acre, at a limit of 160 acres and as long as you developed the resource. Small associations could be formed, but the law forbid large-scale corporate development. What was a big corporation like Standard Oil to do, especially with a tree-hugger like Teddy Roosevelt in office? Have a group of agreeable individuals file the claims as individuals, then buy them out later. Which was precisely the intention when a number of Seattle businessmen and other investors from the western states filed claims on the coalfield. The process of validating the claims and selling out to a firm controlled by Standard was underway — until 1906, when Roosevelt withdrew the lands from the public domain, throwing 900 mineral claims covering some 150,000 acres into legal limbo. Among these claims are included certain groups known as the Greene group, the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company group, the Alaska Development Company group, the Harriman group and the Cunningham group. The first group of filings on this Alaskan land—and these are among the nine hundred awaiting patent—were made for the Alaska Development Company of Seattle, in 1902. They were of the worst type of "dummy entries." A contractor and a Katalla saloonkeeper picked the dummies and paid them $100 each to file on the claims and assign them to the Alaska Development Company. Later, when the government detected this fraud, members of the Alaska Development Company refiled on the same claims. These claims are "believed to be under option to the firm of MacKenzie and Mann, the Canadian financiers said to represent the Standard Oil group, and owners of the Canadian Northern Railway. Standard Oil interests are involved in the Greene group, controlled by former Mayor Harry White, of Seattle, now of California, and by other Seattle men. Simon would appear to be one of those "other Seattle men." In 1907 the Seattle Star blazoned forth on its front page an "expose" of the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company. This corporation, headed by Clarke Davis (according to the Star story-and it has never been gainsaid), a well-known and prosperous citizen of Seattle, had sought for oil in Alaska, and had failed to find it, but had found the now famous coal lands. Then a number of men who had organized the corporation filed, by power of attorney, upon these Alaska coal lands. Each took 160 acres, and all of them transferred their locations to the corporation. Then the corporation issued $5,000,000 of stock in one-dollar shares, basing the value on the ownership of the coal lands. Clarke Davis, said the Star, received one million shares for promotion work and for his own coal locations. Other shares were given to organizers of the corporation, and yet others were placed in the hands of men whose influence would be of value to the company. Many treasury shares were sold at prices ranging from seven cents to forty cents per share. The Star created a sensation by announcing that under the law it is impossible to transfer titles to the location before entry, and that if any plan is entered into to do so the entry is refused and the land becomes again part of the Public Domain. In other words, these lands could not be sold to a corporation for aggregation — which had been the plan from the beginning. A prospectus was issued by the company and widely circulated through the mails. It stated that the company owned 1,920 acres of valuable coal lands in Alaska. Many people invested in stock. Failing legislation that would make their filings legal and give them title to the coal, the directors were in a dilemma. If they proved their claims and assigned them to the company, after taking oath that they were filing on them for their own use, they would be liable to prosecution by the government. And, on the other hand, if the company failed to get possession of the coal lands its officers might be liable to prosecution for the use they had made of the mails. If the individuals who had the claims filed in their names went through with the deal and sold out to Standard, they would be criminals. If Standard failed to get the law changed and acquire the land, they too would be in trouble. Mr. Ballinger was the attorney chosen to relieve this situation and to pilot the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company through legal obstacles to a clear title. He went to Washington and did all in his power in two directions-one to secure the patenting of the lands in dispute, the other to secure broader laws for the use of corporations in grabbing Alaska. The firm of Ballinger, Ronald & Battle, of which Mr. Ballinger was the senior partner until he became connected with the public service, is one of the leading legal forces of Seattle. In the Northwest, Ballinger, Ronald & Battle are generally recognized as the legal representatives of Standard Oil in Seattle. Ballinger adds an agreeable personality to a keen knowledge of the law. He had been Mayor of Seattle and by a war on slot machines had made something of a reputation as a reformer. He had served the government as a lawyer on one or two occasions, and in various ways had attracted the attention of Roosevelt. In March 1907 the President appointed him Commissioner of the General Land Office in Washington. The unpleasant significance of this lies in the fact that Mr. Ballinger was thus in charge of the department which could refuse or consent to patent the Clarke Davis group of coal claims. He took no action on the claims of his clients while he was Commissioner, but his appearance in Washington was immediately followed by the turning of Roosevelt's attention to the question of Alaska coal lands and a message to Congress asking the corporations be permitted to patent considerably larger areas. Ballinger appeared before the Committee on Public Lands for the House of Representatives, and urged the passage of such an act. In referring to the Clarke Davis situation he stated that to his own knowledge the men concerned had been guilty of merely technical violations of the law. The former attorney for one group of coal claimants — the "Cunnigham group" — is appointed by Roosevelt to a post as commissioner of the General Land Office, and immediately he goes to work to loosen restrictions on corporate acquisition of public lands. How quaint. He fails to investigate Standard Oil's move on the claims, brushing off the deal as a minor violation.

In the year 1907 a law was passed and presented to the President, but it was destined to go no further. While it was pending before President Roosevelt, however, Mr. Ballinger was actively at work for it. Meetings were held in Seattle at which men prominent in northwestern business and political circles were present. Among others interested in these conferences were former Governor McGraw, of Washington; H. R. Harriman, an officer of the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company, from whose connection it comes about that these are known as the Harriman claims; John Schram, president of the Washington Trust Company and a trustee of the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company, and F. F. Evans, a mining "broker. Mr. Ballinger was moved to leave his desk in the national capital and go to Seattle and there meet with the conferees. These men used their influence in urging James Garfield, then Secretary of the Interior, to aid in securing the signing of the bill. Mr. Ballinger's friends in Seattle, and he has many of them, have assured me that they could see nothing improper in his thus pushing the claims of his former clients against the very department of the government with which he was officially connected. Indeed, some of his friends explained his participation to me-and they could see no objection to the situation-by the statement that Mr. Ballinger is, or has been, financially interested in 155,000 shares of the stock of the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company. But although the act of 1907 did not get past President Roosevelt, nevertheless, on the twenty-eighth of May 1908, there did go into effect a new law providing that locators who had, in good faith and for their own use, located prior to November 12, 1906, on coal lands in Alaska, might be allowed to combine their holdings to 2,560 acres (four square miles), and work them as a corporation. This might be read in three ways: it might be construed to admit only those that had entered the lands before planning to combine; it might be construed to admit everybody even if their plan to incorporate were made before location; or it might take a middle course and include those that filed in good faith as individuals and then formed a corporation before entering for patent. "We hoped," says a man very close to Ballinger, "to be able to give the statute the broadest possible interpretation so that all locators would be included. We hoped, in fact, to find in it a new rule for construing more broadly the old 64O-acre statute." In the meantime-in March 1908-Mr. Ballinger had resigned his position as Commissioner of the General Land Office. It may, therefore, have been due to his absence from the scene that this law, which Ballinger had helped to pass, contained a truly Rooseveltian last paragraph so strongly antitrust that the purpose of the law was lost. This paragraph, too long to quote, provides that if by any means whatever, tacitly or directly or in any indirect way or in any manner whatever the lands involved become concerned with, or the property of, or in any way connected with any agreement in restraint of trade or any corporation concerned in such an agreement, the lands shall revert to the United States and the title become void. It is said that Gifford Pinchot drafted this paragraph. Part of the coal lands lie in the Chugach Forest Reserve-which would give Mr. Pinchot good reason to take an interest in the legislation. This antitrust paragraph daunted the promoters. Not a single claim has been pressed for entry under this antitrust act and the grabbers are pushing to have it repealed.

And so, as Taft entered office, a new law basically validated the specific situation of the coal claim holders, grandfathering in their right to sell the lands for corporate use. But a final clause added by the Forestry Service's Pinchot — a holdover sympathetic to Roosevelt's conservationist agenda — gave the government the right to take back the land under a very broad set of circumstances. Under Taft, Ballinger was appointed Secretary of the Interior (shades of James Watt). After releasing certain lands for development that Pinchot had worked to safeguard under Roosevelt, Pinchot went on the offensive. In November of 1909, an article in Collier's (with Pinchot as the source) accused Ballinger of overlooking collusion in his official dealings with the coal claimants. Though soon cleared of wrongdoing by the Taft administration, he was dogged by the allegations for the rest of his life. Taft canned Pinchot for insubordination. So, really, for all we know, Simon was a sucker who bought some shares in a coal field. Or he was a Seattle heavyweight who almost got in over his head. Getting hold of the report will tell us more.

According to Taft's attorney general, George Wickersham, the effects of the affair were tumultuous: The 1910 Ballinger-Pinchot affair, which involved the illegal distribution of thirty-three federal government Alaskan coal land claims to the Guggenheim interests, culminated in a Congressional investigation and brought Alaska directly into the national headlines. Wickersham, surveying the fallout of the affair, determined that it destroyed the friendship between Theodore Roosevelt and President Taft; split the Republican party into two great factions; defeated President Taft for re-election in 1912; elected Woodrow Wilson President of the United States; and changed the course of history of our country. A chastened President Taft, in a special message to Congress on February 2, 1912, urged the enactment of legislation which would help Alaska develop its resources along the lines that Wickersham had urged. Heavy. Roosevelt was so peeved at Taft about the whole situation that he ran against him in the next election as candidate for the Progressive party, splitting the Republicans and ushering Woodrow Wilson into the presidency.

So, apparently, Simon bought some shares in a coal field from agent Simmonds, one of the deal's inner circle. What happened to his interest in the land is unknown, but according to the Brandeis Law School Library: (Ironically, surveys of the Cunningham lands later showed that the lands had little coal.) |